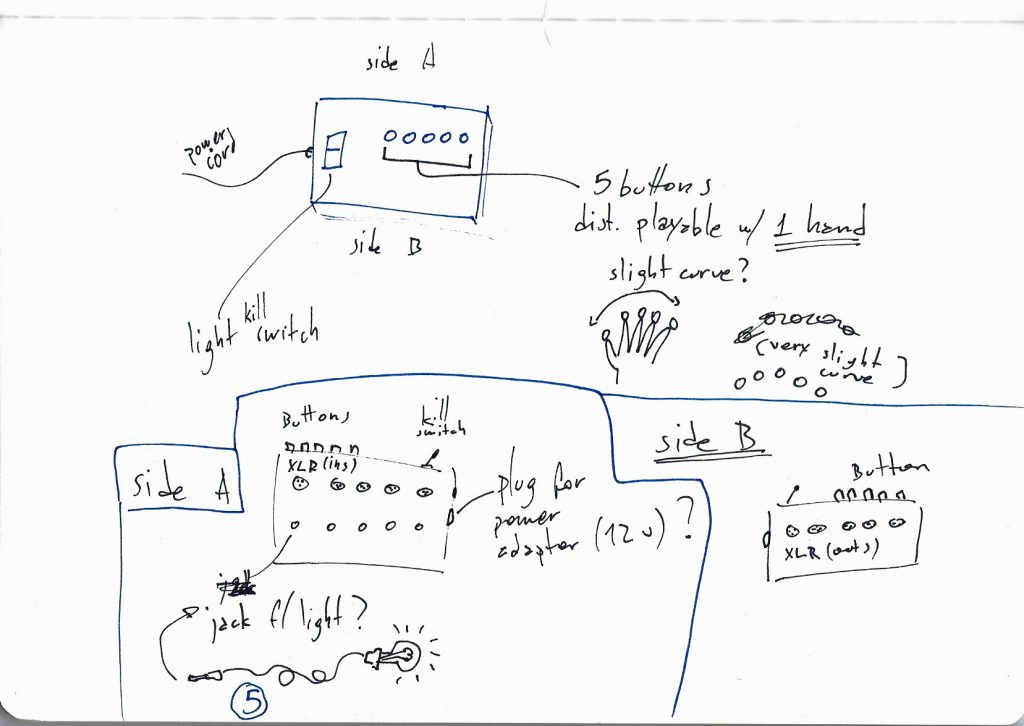

in steps (2018-2019) is a piece for for 5 amplified voices and 1 performer by Ricardo Eizirik. Although six people are on stage, only one of these is in control of the sounds. The first performance of this piece was done by the Neue Vocalsolisten Stuttgart and Guillermo Anzorena played the controller part. The controller is a self-built device, which is able to turn the microphone of each singer on and off. As Ricardo told me, he wanted to “keep it simple” and do a piece without a computer. And although he realised that a Max patch [a music software] might have been an easier option in the end, the use of this controller makes some very special features possible.

Ricardo’s inspiration for this piece is a step sequencer (hence the title of the piece), and how you can smoothly progress from one sound pattern to the next one with this device. He looked for a slightly less accurate, slightly more organic step sequencer than the ones we commonly use. So instead of using samples or electronic sounds he used singers for providing the sounds one steps through. Each key of the controller is connected as an on-off switch to one of the five microphones in front of the singers.

The controller itself is a bit similar to a very simplified piano keyboard. But a piano has a key for each sound, resulting in 88 keys for 88 pitches. The instrument developed by Ricardo could be considered to be a very flexible “synthesiser”, controlling many different sounds with just five keys. It can play chords, glissandi, but also produce all kinds of noises and make transitions between these sounds. In short: all sounds the human voice can produce. Ricardo uses one simple trick to turn all these utterances by human voices into seemingly electronic sounds. He leaves the attacks unamplified. The singers start to sing or make noise before Guillermo pushes their amplification key on the controller on and end after he has released the key again.

When creating electronic sounds which should sound similar to acoustical instruments one of the main difficulties is to create the transients of the attack. When you play the violin, at the beginning of a sound there is some noise of the bow touching the string, the string coming into motion etc. All these changes are the most difficult to simulate in a synthesised sound. This is one of the reasons why it is often quite easy to distinguish between a trumpet recording and a synthesised trumpet sound, for example. Also, when cutting of the attack of a piano tone, it is nearly impossible to recognise that the original recording is a piano sound (Pierre Schaeffer proves this in his Solfège de l’objet sonore in 1967, for example). Ricardo is making an advantage of this by using the inverted idea: he tries to make a synthesiser out of human voices, instead of making synthesised versions of conventional instruments. Due to using the controller all voice sounds have an “electronic” attack.

What adds to the idea of an electronic instrument being played instead of the voices of the singers being amplified is the deliberately harsh way the amplification is turned on and off. Commonly you would avoid turning microphone channels on and off without fading in or out, because it might cause clicks and cracks. But Ricardo told me, one of the reasons for him why the controller convinced him, and not the Max patch, was because of those noises caused by switching on and off: you hear how this step sequencer is controlled. Even the control mechanism itself is audible. You can here the metal of the keys clicking when Guillermo plays a quick solo (9:05 in the video at the end of this post).

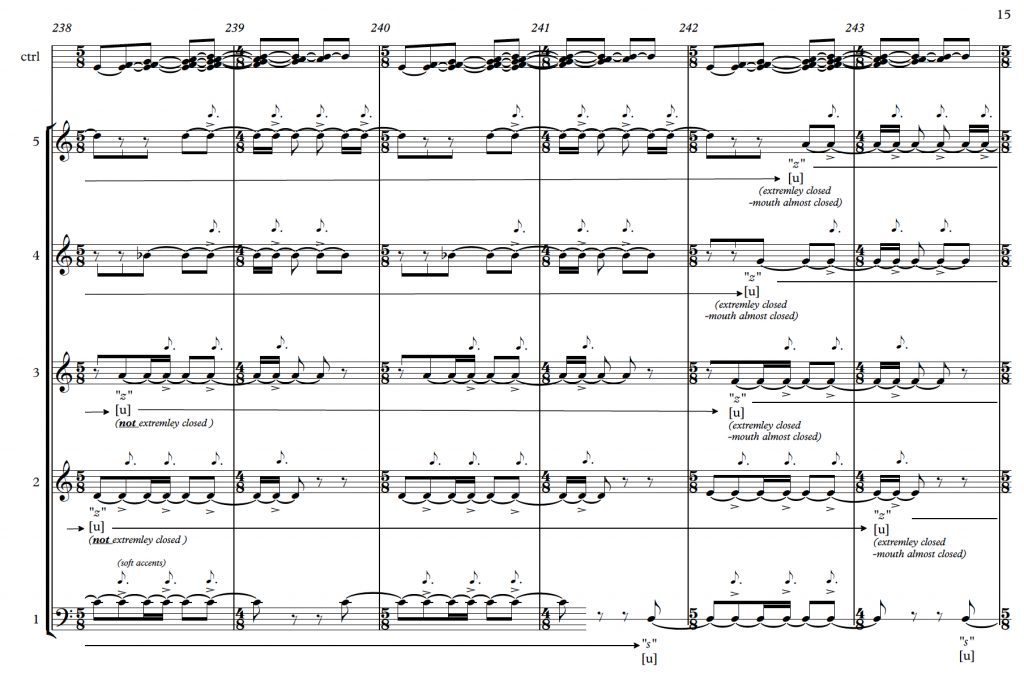

The piece also starts with a solo for the controller played by Guillermo. You hear the channels being connected and the amplified noise of the performance space. Each singer now hits their microphone, making them audible. To see what microphone is amplified red LED lights are used. These lights not only make it easier for the audience to recognise which microphone is amplified but also give the set-up even more a “step-sequencer” character. From 0:25 onwards the singers make soft noises, barely audible without amplification, and Guillermo controls the amplification according to the score:

Performing under these conditions the singers loose control of the moment they will become audible for the audience. They have to sing softly, and it is impossible for them to predict how they will sound when amplified. By adding pitched material and different kinds of noises, and from 4:25 onwards also the text “a step is a step is a step is a …” the step sequencer is filled with a variety of different sounds. Remarkable is for example the switch from noisy sounds to pitches in between 6:50 to 7:10. Guillermo continues to play the same sequence of key strokes, but the singers suddenly switch from noise to pitches. What follows now is possibly the most electronic-like part of the piece, in which you hear a weird amalgam of voices and some classical synthesiser sounds.

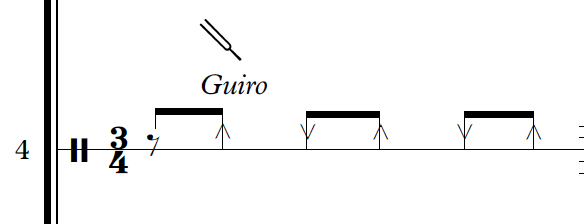

During the piece the microphones itself are also played directly. The tuning fork is a standard gadget for singers notated down in scores, and Ricardo decided to use these tuning forks also in different ways in the piece. The gooseneck microphones Ricardo uses are played similar to how the musical instrument güiro is played; the singers rub the tuning forks along the neck of the microphone.

Sometimes, the singers place the tuning forks on the microphones, so instead of having the voice as an input now a tuning fork sound is heard (9:35 for example). Especially in combination with the key controller this reminded me a bit of the device—Apparat zur künstlichen Zusammensetzung der Vocalklänge—Hermann von Helmholtz developed (see also chapter three of my book for a longer account on Helmholtz, tuning forks and microphones and loudspeakers).

Looking at the set-up for this piece much of the technology was already available around the 1930s. The beauty lies exactly in the remnants of this piece’s technology of the early years of connecting wires and transferring signals. Where as clicks and cracks are often sign of malfunctioning connections, the clicks and cracks in Ricardo’s piece are reveal that these noises also signify us that there is a connection and that you are amplified. And whereas in our daily life technology often wants us to believe we have left the early age of sound technology, and have an electronic life without any disturbances, Ricardo’s piece proposes to give the clicks and cracks their own place in life.

This video documents a performance of in steps by the Neue Vocalsolisten Stuttgart (from left to right: Guillermo Anzorena, Andreas Fischer, Martin Nagy, Truike van der Poel, Susanne Leitz-Lorey and Johanna Zimmer.